Right Now | Eight Is Enough

Star Power in Politics

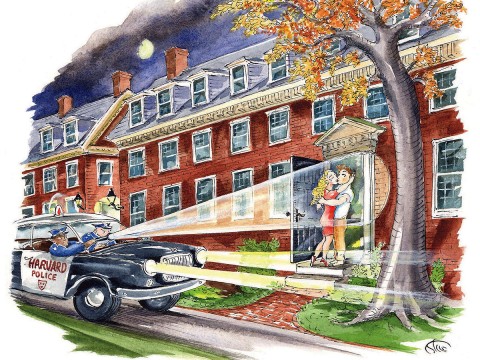

Why do people vote for celebrities? When surveyed, voters say that they prefer elected representatives who are not famous for reasons unrelated to politics. Yet actors, sports figures, TV commentators, and authors, for example, frequently win elections. Because nothing is more fundamental to democracy than casting a vote, the question of how voters choose among candidates—and the extent to which name recognition influences that choice—is both important and poorly understood, says Justin Reeves, a postdoctoral fellow in the program on U.S.–Japan relations at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs (WCFIA).

Candidates often “dedicate considerable resources to getting their names out in public using flyers, yard signs, and stickers”—outreach that is “often totally devoid of policy content,” said Reeves, who has written about electoral reform in advanced democracies, and is currently studying the causes and consequences of celebrity engagement in politics. In a lecture this spring, he argued that even such simple name recognition can, in fact, boost support for a candidate—but whether it does or not is heavily influenced by the electoral system.

The general assumption among political scientists, he stated, has been that name recognition matters only in “low information elections,” in which voters know or care little to nothing about candidates’ policy platforms. The idea is that if voters are concerned about candidates’ stands on the issues, or their incumbency or ideology, they won’t cast their vote based on “a simple cue like mere recognition. But we know from extensive studies in psychology and decision theory,” Reeves said, that people don’t always use the most relevant information to make decisions. In certain circumstances, they gravitate toward the least intellectually demanding approach.

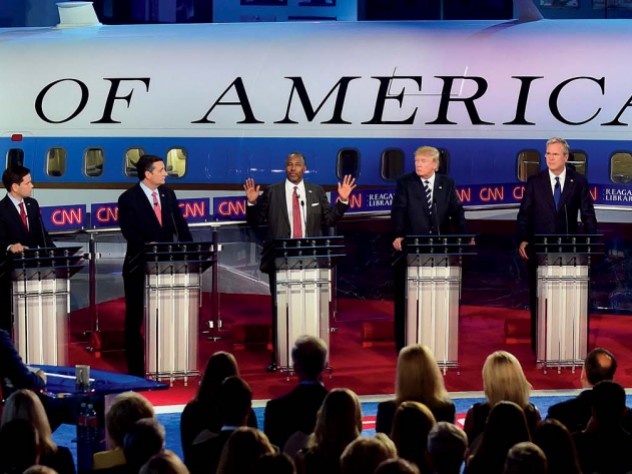

Because individuals experience a kind of cognitive overload when faced with many choices that are hard to tell apart, Reeves hypothesized that when many candidates from the same party are running against each other, mere recognition would be more likely to affect the outcome of elections. Faced with a plethora of indistinguishable choices, many voters may abstain; those who do vote may be influenced by name recognition or even irrelevant details such as ballot order. If his theory is true, one reason to care about it, he said, is that such circumstances occur frequently in U.S. primaries (the 2016 Republican presidential slate, for example), and are even more common in countries such as Japan, Finland, Brazil, and Greece, where electoral rules can lead to elections with slates of 50 to 200 candidates.

Using data from Japan spanning from 1962 to 2013, Reeves found that when celebrities ran for seats in the upper house in national legislative elections (which have high levels of intraparty competition), they won more than half the time. But in elections for the same office run at the local (prefectural) level, which are held under different electoral rules involving fewer candidates and greater competition between parties, celebrities won less than a third of the time. When surveyed, Japanese voters overwhelmingly reject celebrities in the abstract, so the data, Reeves said, suggest “a disconnect between what voters say they want and what they end up doing in the voting booth.” Electoral rules that lead to large numbers of candidates from a single party, Reeves argued, create the conditions that favor the famous—thus “leading to outcomes that are at odds with voters’ own stated preferences.”

To see if his findings would hold up in other democracies with long ballots of like-minded candidates, Reeves analyzed election data from Finland from 2003 to 2011. There, too, he found that celebrity candidates enjoyed a significant advantage in a crowded field. He then tried an experiment, asking Japanese survey subjects to participate in a hypothetical election in which all the candidates came from the party they most frequently supported. One group received a ballot with just three candidates, including one celebrity. The second group received a ballot with nine names, including one celebrity. For each candidate, Reeves supplied a photograph and educational and occupational background information. In his two corresponding control groups, he replaced the celebrity with a different name and face, but identical background information.

Celebrity status, he found, did not influence the results on the short ballots. But on the long ballots, celebrities not only did better than all their opponents, they received triple the support of their control-group counterparts with identical backgrounds. And among the voters, Reeves found no differences by gender, age, and levels of education, income, and political engagement in people’s willingness to support celebrity candidates. “This suggests,” he said, “that even a modest increase in cognitive demand can influence the way many people—not just those who are less politically sophisticated—make ballot decisions.” And it suggests that, in democracies around the world, electoral reforms that allow voters to choose among smaller numbers of candidates might lead to more thoughtful outcomes.

.jpg)

.jpg)